Charles Stuart Parnell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an

Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP)

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members often ...

from 1875 to 1891, also acting as Leader of the Home Rule League

The Home Rule League (1873–1882), sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was an Irish political party which campaigned for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, until it was replaced by the Irish Parliam ...

from 1880 to 1882 and then Leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish national ...

from 1882 to 1891. His party held the balance of power in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

during the Home Rule debates of 1885–1886.

Born into a powerful Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

landowning family in County Wicklow

County Wicklow ( ; ga, Contae Chill Mhantáin ) is a county in Ireland. The last of the traditional 32 counties, having been formed as late as 1606, it is part of the Eastern and Midland Region and the province of Leinster. It is bordered by t ...

, he was a land reform agitator and founder of the Irish National Land League

The Irish National Land League (Irish: ''Conradh na Talún'') was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which sought to help poor tenant farmers. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farmer ...

in 1879. He became leader of the Home Rule League

The Home Rule League (1873–1882), sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was an Irish political party which campaigned for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, until it was replaced by the Irish Parliam ...

, operating independently of the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

, winning great influence by his balancing of constitutional, radical, and economic issues, and by his skillful use of parliamentary procedure. He was imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol

Kilmainham Gaol ( ga, Príosún Chill Mhaighneann) is a former prison in Kilmainham, Dublin, Ireland. It is now a museum run by the Office of Public Works, an agency of the Government of Ireland. Many Irish revolutionaries, including the leade ...

, Dublin, in 1882, but he was released when he renounced violent extra-Parliamentary action. The same year, he reformed the Home Rule League as the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish national ...

, which he controlled minutely as Britain's first disciplined democratic party.

The hung parliament

A hung parliament is a term used in legislatures primarily under the Westminster system to describe a situation in which no single political party or pre-existing coalition (also known as an alliance or bloc) has an absolute majority of legisl ...

of 1885

Events

January–March

* January 3– 4 – Sino-French War – Battle of Núi Bop: French troops under General Oscar de Négrier defeat a numerically superior Qing Chinese force, in northern Vietnam.

* January 4 – ...

saw him hold the balance of power between William Gladstone's Liberal Party and Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

's Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

. His power was one factor in Gladstone's adoption of Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

as the central tenet of the Liberal Party. Parnell's reputation peaked from 1889 to 1890, after letters published in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'', linking him to the Phoenix Park killings

The Phoenix Park Murders were the fatal stabbings of Lord Frederick Cavendish and Thomas Henry Burke in Phoenix Park, Dublin, Ireland, on 6 May 1882. Cavendish was the newly appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland and Burke was the Permanent ...

of 1882, were shown to have been forged by Richard Pigott

Richard Pigott (1835 – 1 March 1889) was an Irish journalist, best known for his forging of evidence that Charles Stewart Parnell of the Irish National Land League had been sympathetic to the perpetrators of the Phoenix Park Murders. Par ...

. The Irish Parliamentary Party split in 1890, following the revelation of Parnell's long adulterous love affair, which led to many British Liberals (a number of them Nonconformists) refusing to work with him, and engendered strong opposition to him from Catholic bishops. He headed a small minority faction until his death in 1891.

Parnell is celebrated as the best organiser of an Irish political party up to that time, and one of the most formidable figures in parliamentary history. Despite this noted talent for politics, his career eventually became mired in a personal scandal from which his image never recovered and ultimately he was unable to secure his lifelong goal of obtaining Irish Home Rule.

Early life

Charles Stewart Parnell was born inAvondale House

Avondale House, in Avondale, County Wicklow, Ireland, is the birthplace and home of Charles Stewart Parnell. It is set in the Avondale Forest Park, spanning over 2 km2 (500 acres) of land, approximately 1.5 km from the nearby town o ...

, County Wicklow. He was the third son and seventh child of John Henry Parnell

John Henry Parnell (14 August 1811 – 3 August 1859) was an Anglo-Irish cricketer with amateur status who was active in 1831. He was born in Avondale, County Wicklow and died in Dublin. He made his first-class debut in 1831 and appeared in one ...

(1811–1859), a wealthy Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

landowner, and his American wife Delia Tudor Stewart (1816–1898) of Bordentown, New Jersey

Bordentown is a city in Burlington County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the city's population was 3,924.Charles Stewart (the stepson of one of

Whilst in gaol, Parnell moved in April 1882 to make a deal with the government, negotiated through Captain

Whilst in gaol, Parnell moved in April 1882 to make a deal with the government, negotiated through Captain

Parnell now sought to use his experience and huge support to advance his pursuit of Home Rule and resurrected the suppressed Land League, on 17 October 1882, as the

Parnell now sought to use his experience and huge support to advance his pursuit of Home Rule and resurrected the suppressed Land League, on 17 October 1882, as the  Parnell next turned to the Home Rule League Party, of which he was to remain the re-elected leader for over a decade, spending most of his time at

Parnell next turned to the Home Rule League Party, of which he was to remain the re-elected leader for over a decade, spending most of his time at

During the period 1886–90, Parnell continued to pursue Home Rule, striving to reassure British voters that it would be no threat to them. In Ireland, unionist resistance (especially after the Irish Unionist Party was formed) became increasingly organised. Parnell pursued moderate and conciliatory tenant land purchase and still hoped to retain a sizeable landlord support for home rule. During the agrarian crisis, which intensified in 1886 and launched the

During the period 1886–90, Parnell continued to pursue Home Rule, striving to reassure British voters that it would be no threat to them. In Ireland, unionist resistance (especially after the Irish Unionist Party was formed) became increasingly organised. Parnell pursued moderate and conciliatory tenant land purchase and still hoped to retain a sizeable landlord support for home rule. During the agrarian crisis, which intensified in 1886 and launched the

online

* Foster, R. F. ''Vivid Faces: The Revolutionary Generation in Ireland, 1890–1923'' (2015

excerpt

* Harrison's two books defending Parnell were published in 1931 and 1938. They have had a major impact on Irish historiography, leading to a more favourable view of Parnell's role in the O'Shea affair. commented that Harrison "did more than anyone else to uncover what seems to have been the true facts" about the Parnell-O'Shea liaison. * * León Ó Broin. ''Parnell'' (Dublin: Oifig an tSoláthair 1937) * Kee, Robert. ''The Green Flag'', (Penguin, 1972) * * * Lyons, F. S. L. ''. The Fall of Parnell, 1890–91'' (1960

online

* McCarthy, Justin, ''A History of Our Own Times'' (Vols. I–IV 1879–1880; Vol. V 1897); reprinted in paperback i.a. by

When Parnell was rejected by the majority of his parliamentary party, McCarthy assumed its chairmanship, a position which he held until 1896.

The Parnell Society

website

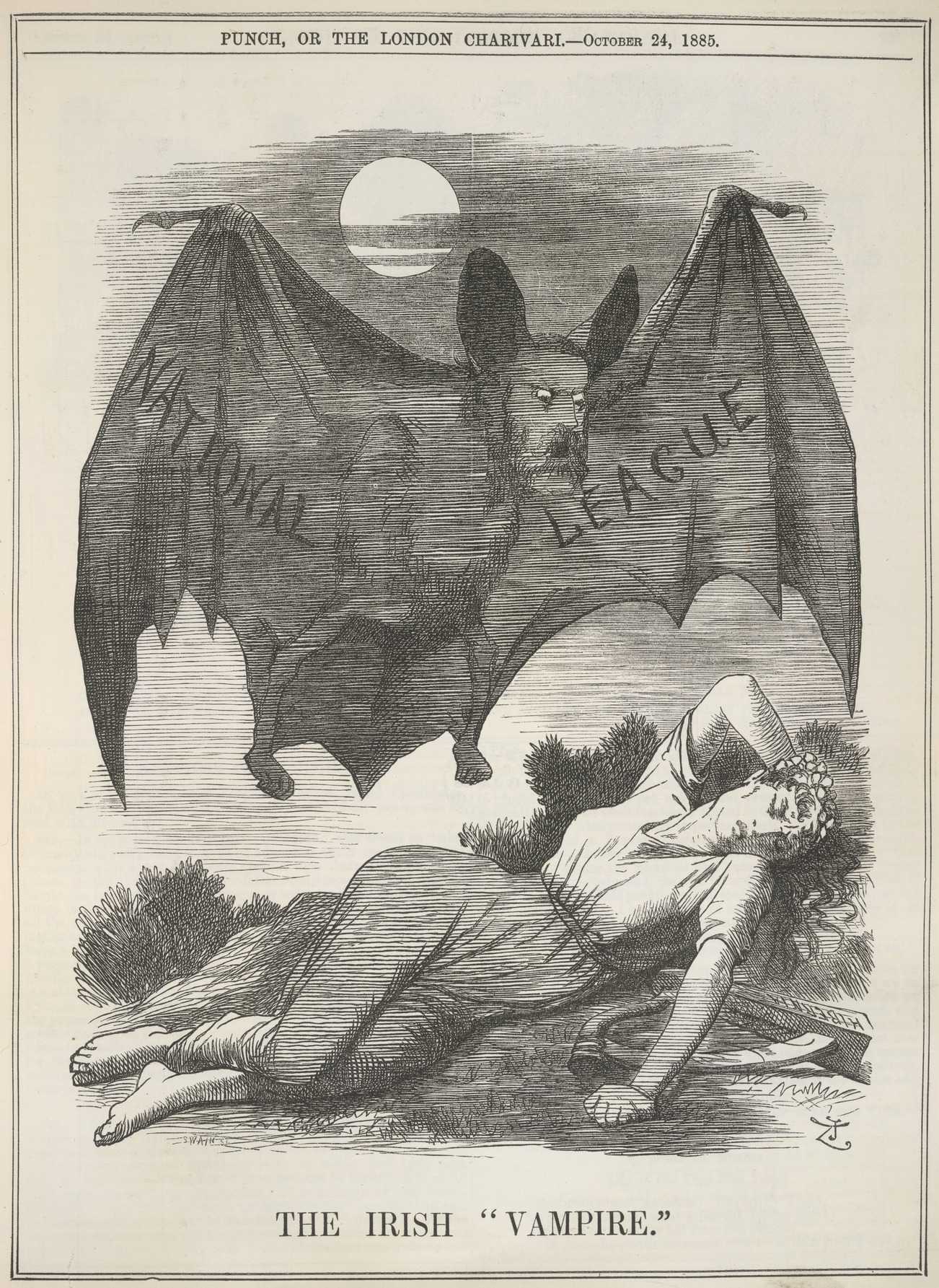

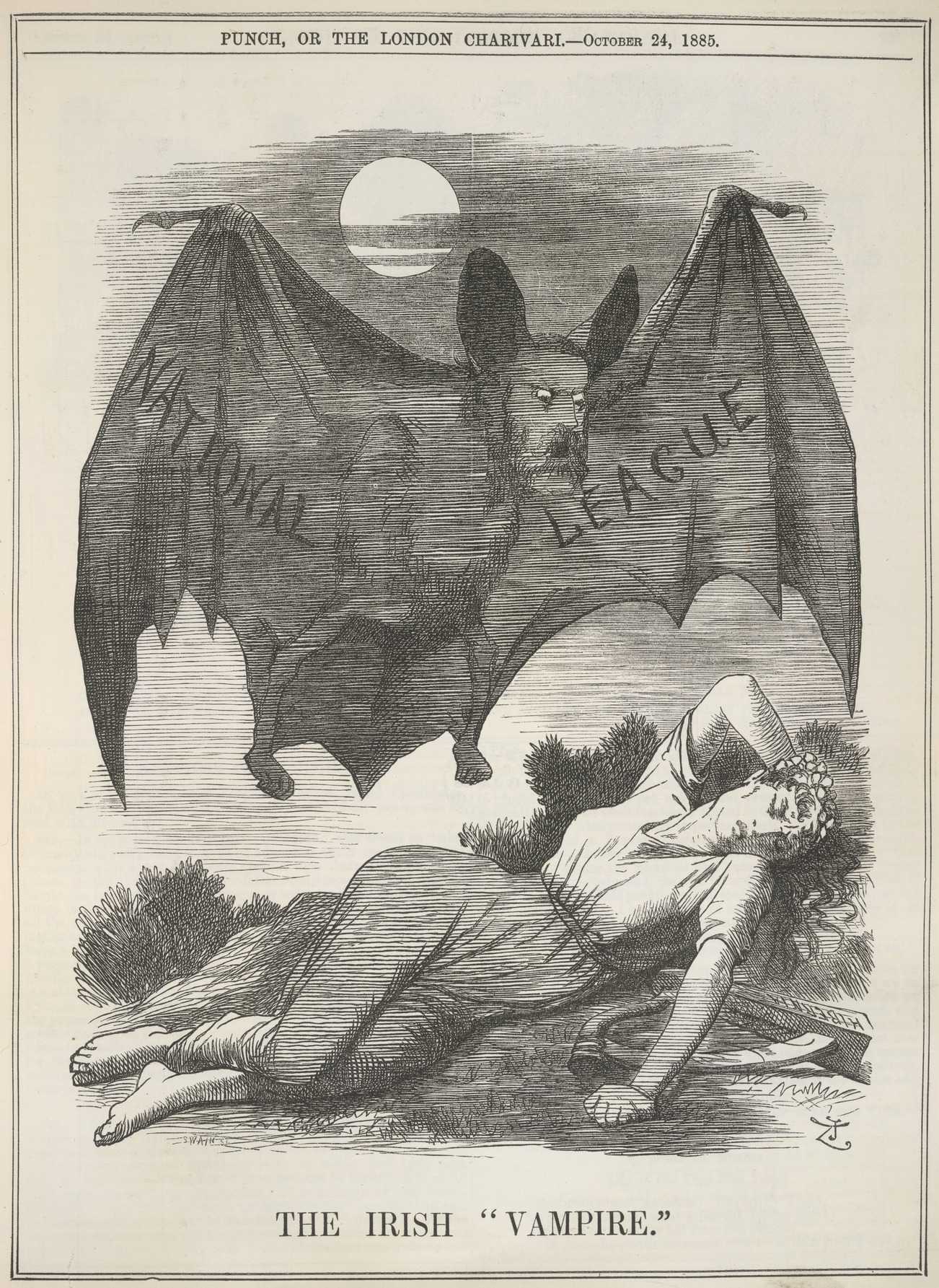

Charles Parnell Caricature by Harry Furniss – UK Parliament Living Heritage

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Parnell, Charles Stewart 1846 births 1891 deaths Alumni of Magdalene College, Cambridge Burials at Glasnevin Cemetery High Sheriffs of Wicklow Home rule in Ireland Home Rule League MPs Irish Anglicans Irish expatriates in England Irish land reform activists Irish Parliamentary Party MPs Irish people of American descent Irish people of English descent Irish people of Scottish descent Irish people of Welsh descent Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Cork City Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Mayo constituencies (1801–1922) Parnellite MPs Patrons of the Gaelic Athletic Association Political scandals in Ireland Political scandals in the United Kingdom Politicians from County Wicklow Protestant Irish nationalists UK MPs 1874–1880 UK MPs 1880–1885 UK MPs 1885–1886 UK MPs 1886–1892 Deaths from pneumonia in England

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

's bodyguards). There were eleven children in all: five boys and six girls. Admiral Stewart's mother, Parnell's great-grandmother, belonged to the Tudor family, so Parnell had a distant relationship with the British Royal Family. John Henry Parnell himself was a cousin of one of Ireland's leading aristocrats, Viscount Powerscourt

Viscount Powerscourt ( ) is a title that has been created three times in the Peerage of Ireland, each time for members of the Wingfield family. It was created first in 1618 for the Chief Governor of Ireland, Richard Wingfield. However, this creat ...

, and also the grandson of a Chancellor of the Exchequer in Grattan's Parliament

The Constitution of 1782 was a group of Acts passed by the Parliament of Ireland and the Parliament of Great Britain in 1782–83 which increased the legislative and judicial independence of the Kingdom of Ireland by reducing the ability of th ...

, Sir John Parnell, who lost office in 1799, when he opposed the Act of Union.

The Parnells of Avondale were descended from a Protestant English merchant family, which came to prominence in Congleton

Congleton is a town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. The town is by the River Dane, south of Manchester and north of Stoke on Trent. At the 2011 Census, it had a population of 26,482.

Top ...

, Cheshire, early in the 17th century where as Baron Congleton two generations held the office of Mayor of Congleton before moving to Ireland. The family produced a number of notable figures, including Thomas Parnell

Thomas Parnell (11 September 1679 – 24 October 1718) was an Anglo-Irish poet and clergyman who was a friend of both Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift.

He was born in Dublin, the eldest son of Thomas Parnell (died 1685) of Maryborough, Queen' ...

(1679–1718), the Irish poet, and Henry Parnell, 1st Baron Congleton

Henry Brooke Parnell, 1st Baron Congleton PC (3 July 1776 – 8 June 1842), known as Sir Henry Parnell, Bt, from 1812 to 1841, was an Irish writer and Whig politician. He was a member of the Whig administrations headed by Lord Grey and Lord ...

(1776–1842), the Irish politician. Parnell's grandfather William Parnell (1780–1821), who inherited the Avondale Estate in 1795, was an Irish liberal Party MP for Wicklow

Wicklow ( ; ga, Cill Mhantáin , meaning 'church of the toothless one'; non, Víkingaló) is the county town of County Wicklow in Ireland. It is located south of Dublin on the east coast of the island. According to the 2016 census, it has ...

from 1817 to 1820. Thus, from birth, Charles Stewart Parnell possessed an extraordinary number of links to many elements of society; he was linked to the old Irish Parliamentary tradition via his great-grandfather and grandfather, to the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

via his grandfather, to the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

(where his grandfather Charles Stewart (1778–1869)

Charles Stewart (28 July 1778 – 6 November 1869) was an officer in the United States Navy who commanded a number of US Navy ships, including . He saw service during the Quasi War and both Barbary Wars in the Mediterranean along North Africa and t ...

had been awarded a gold medal by the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

for gallantry in the U.S. Navy). Parnell belonged to the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second ...

, disestablished in 1868 (its members mostly unionists) though in later years he began to drop away from formal church attendance; and he was connected with the aristocracy through the Powerscourts. Yet it was as a leader of Irish Nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

that Parnell established his fame.

Parnell's parents separated when he was six, and as a boy he was sent to different schools in England, where he spent an unhappy youth. His father died in 1859 and he inherited the Avondale estate, while his older brother John inherited another estate in County Armagh

County Armagh (, named after its county town, Armagh) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the southern shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of and ha ...

. The young Parnell studied at Magdalene College, Cambridge

Magdalene College ( ) is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1428 as a Benedictine hostel, in time coming to be known as Buckingham College, before being refounded in 1542 as the College of St Mary ...

(1865–69) but, due to the troubled financial circumstances of the estate he inherited, he was absent a great deal and never completed his degree. In 1871, he joined his elder brother John Howard Parnell

John Howard Parnell (1843 – 3 May 1923) was an older brother of the Irish Nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell and after his brother's death was himself a Parnellite Nationalist Member of Parliament, for South Meath from 1895 to 1900. ...

(1843–1923), who farmed in Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

(later an Irish Parnellite MP and heir to the Avondale estate), on an extended tour of the United States. Their travels took them mostly through the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

and apparently the brothers neither spent much time in centres of Irish immigration nor sought out Irish-Americans.

In 1874, he became High Sheriff of Wicklow

The High Sheriff of Wicklow was the British Crown's judicial representative in County Wicklow, Ireland from Wicklow's formation in 1606 until 1922, when the office was abolished in the new Free State and replaced by the office of Wicklow County Sh ...

, his home county in which he was also an officer in the Wicklow militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

. He was noted as an improving landowner who played an important part in opening the south Wicklow area to industrialisation. His attention was drawn to the theme dominating the Irish political scene of the mid-1870s, Isaac Butt

Isaac Butt (6 September 1813 – 5 May 1879) was an Irish barrister, editor, politician, Member of Parliament in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, economist and the founder and first leader of a number of Irish nationalist parti ...

's Home Rule League

The Home Rule League (1873–1882), sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was an Irish political party which campaigned for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, until it was replaced by the Irish Parliam ...

formed in 1873 to campaign for a moderate degree of self-government. It was in support of this movement that Parnell first tried to stand for election in Wicklow, but as high sheriff was disqualified. He failed again in 1874 as home rule candidate in a County Dublin

"Action to match our speech"

, image_map = Island_of_Ireland_location_map_Dublin.svg

, map_alt = map showing County Dublin as a small area of darker green on the east coast within the lighter green background of ...

by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

.

Flynn argues that the primary reason Parnell joined the Irish cause was his "implacable hostility towards England," which probably was founded on grievances from his school days, and his mother's hostility toward England.

Political career

On 17 April 1875, Parnell was first elected to theHouse of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

in a by-election for Meath, as a Home Rule League MP, backed by Fenian

The word ''Fenian'' () served as an umbrella term for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and their affiliate in the United States, the Fenian Brotherhood, secret political organisations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries dedicated ...

Patrick Egan. He replaced the deceased League MP, veteran Young Irelander John Martin. Parnell later sat for the constituency of Cork City

Cork ( , from , meaning 'marsh') is the second largest city in Ireland and third largest city by population on the island of Ireland. It is located in the south-west of Ireland, in the province of Munster. Following an extension to the city' ...

, from 1880 until 1891.

During his first year as an MP, Parnell remained a reserved observer of parliamentary proceedings. He first came to attention in the public eye in 1876, when he claimed in the House of Commons that he did not believe that any murder had been committed by Fenians in Manchester. That drew the interest of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

(IRB), a physical force

In physics, a force is an influence that can change the motion of an Physical object, object. A force can cause an object with mass to change its velocity (e.g. moving from a Newton's first law, state of rest), i.e., to accelerate. Force can ...

Irish organisation that had staged a rebellion in 1867. Parnell made it his business to cultivate Fenian sentiments both in Britain and Ireland and became associated with the more radical wing of the Home Rule League, which included Joseph Biggar

Joseph Gillis Biggar (c. 1828 – 19 February 1890), commonly known as Joe BiggarD.D. Sheehan, Ireland Since Parnell', London: Daniel O'Connor, 1921. or J. G. Biggar, was an Irish nationalist politician from Belfast. He served as an MP in the H ...

(MP for Cavan

Cavan ( ; ) is the county town of County Cavan in Ireland. The town lies in Ulster, near the border with County Fermanagh in Northern Ireland. The town is bypassed by the main N3 road that links Dublin (to the south) with Enniskillen, Bally ...

from 1874), John O'Connor Power

John O'Connor Power (13 February 1846 – 21 February 1919) was an Irish Fenian and a Home Rule League and Irish Parliamentary Party politician and as MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland represented Ma ...

(MP for County Mayo

County Mayo (; ga, Contae Mhaigh Eo, meaning "Plain of the Taxus baccata, yew trees") is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. In the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Conn ...

from 1874) (both, although constitutionalists, had links with the IRB), Edmund Dwyer-Gray

Edmund John Chisholm Dwyer-Gray (2 April 18706 December 1945) was an Irish-Australian politician, who was the 29th Premier of Tasmania from 11 June to 18 December 1939. He was a member of the Australian Labor Party (ALP).

Early life

He was bo ...

(MP for Tipperary

Tipperary is the name of:

Places

*County Tipperary, a county in Ireland

**North Tipperary, a former administrative county based in Nenagh

**South Tipperary, a former administrative county based in Clonmel

*Tipperary (town), County Tipperary's na ...

from 1877), and Frank Hugh O'Donnell

Frank Hugh O'Donnell (also Frank Hugh O'Cahan O'Donnell), born Francis Hugh MacDonald (9 October 1846 – 2 November 1916) was an Irish writer, journalist and nationalist politician.

Early life

O'Donnell was born in an army barracks in Devon, E ...

(MP for Dungarvan

Dungarvan () is a coastal town and harbour in County Waterford, on the south-east coast of Ireland. Prior to the merger of Waterford County Council with Waterford City Council in 2014, Dungarvan was the county town and administrative centre of ...

from 1877). He engaged with them and played a leading role in a policy of obstructionism

Obstructionism is the practice of deliberately delaying or preventing a process or change, especially in politics.

As workplace aggression

An obstructionist causes problems. Neuman and Baron (1998) identify obstructionism as one of the three dim ...

(i.e., the use of technical procedures to disrupt the House of Commons' ability to function) to force the House to pay more attention to Irish issues, which had previously been ignored. Obstruction involved giving lengthy speeches which were largely irrelevant to the topic at hand. This behaviour was opposed by the less aggressive chairman (leader) of the Home Rule League, Isaac Butt

Isaac Butt (6 September 1813 – 5 May 1879) was an Irish barrister, editor, politician, Member of Parliament in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, economist and the founder and first leader of a number of Irish nationalist parti ...

.

Parnell visited the United States that year, accompanied by O'Connor Power. The question of Parnell's closeness to the IRB, and whether indeed he ever joined the organisation, has been a matter of academic debate for a century. The evidence suggests that later, following the signing of the Kilmainham Treaty

The Kilmainham Treaty was an informal agreement reached in May 1882 between Liberal British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone and the Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell. Whilst in gaol, Parnell moved in April 1882 to make a ...

, Parnell did take the IRB oath, possibly for tactical reasons. What is known is that IRB involvement in the League's sister organisation, the ''Home Rule Confederation of Great Britain'', led to the moderate Butt's ousting from its presidency (even though he had founded the organisation) and the election of Parnell in his place, on 28 August 1877. Parnell was a restrained speaker in the House of Commons, but his organisational, analytical and tactical skills earned wide praise, enabling him to take on the presidency of the British organisation. Butt died in 1879, and was replaced as chairman of the Home Rule League by the Whig-oriented William Shaw. Shaw's victory was only temporary.

New departure

From August 1877, Parnell held a number of private meetings with prominentFenian

The word ''Fenian'' () served as an umbrella term for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and their affiliate in the United States, the Fenian Brotherhood, secret political organisations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries dedicated ...

leaders. He visited Paris, France, where he met John O'Leary and J. J. O'Kelly both of whom were impressed by him and reported positively to the most capable and militant Leader of the American republican Clan na Gael

Clan na Gael ( ga, label=modern Irish orthography, Clann na nGael, ; "family of the Gaels") was an Irish republican organization in the United States in the late 19th and 20th centuries, successor to the Fenian Brotherhood and a sister org ...

organisation, John Devoy

John Devoy ( ga, Seán Ó Dubhuí, ; 3 September 1842 – 29 September 1928) was an Irish republican rebel and journalist who owned and edited ''The Gaelic American'', a New York weekly newspaper, from 1903 to 1928.

Devoy dedicated over 60 ...

. In December 1877, at a reception for Michael Davitt

Michael Davitt (25 March 184630 May 1906) was an Irish republican activist for a variety of causes, especially Home Rule and land reform. Following an eviction when he was four years old, Davitt's family migrated to England. He began his caree ...

on his release from prison, he met William Carrol who assured him of Clan na Gael's support in the struggle for Irish self-government. This led to a meeting in March 1878 between influential constitutionalists, Parnell and Frank Hugh O'Donnell, and leading Fenians O'Kelly, O'Leary and Carroll. This was followed by a telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

from John Devoy in October 1878 which offered Parnell a " New Departure" deal of separating militancy from the constitutional movement as a path to all-Ireland self-government, under certain conditions: abandonment of a federal solution in favour of separatist self-government, vigorous agitation in the land question on the basis of peasant proprietorship, exclusion of all sectarian issues, collective voting by party members and energetic resistance to coercive legislation.

Parnell preferred to keep all options open without clearly committing himself when he spoke in 1879 before Irish Tenant Defence Associations at Ballinasloe

Ballinasloe ( ; ) is a town in the easternmost part of County Galway in Connacht. Located at an ancient crossing point on the River Suck, evidence of ancient settlement in the area includes a number of Bronze Age sites. Built around a 12th-ce ...

and Tralee

Tralee ( ; ga, Trá Lí, ; formerly , meaning 'strand of the Lee River') is the county town of County Kerry in the south-west of Ireland. The town is on the northern side of the neck of the Dingle Peninsula, and is the largest town in County ...

. It was not until Davitt persuaded him to address a second meeting at Westport, County Mayo

Westport (, historically anglicised as ''Cahernamart'') is a town in County Mayo in Ireland.Westport Before 1800 by Michael Kelly published in Cathair Na Mart 2019 It is at the south-east corner of Clew Bay, an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean on th ...

in June that he began to grasp the potential of the land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

movement. At a national level several approaches were made which eventually produced the "New Departure" of June 1879, endorsing the foregone informal agreement which asserted an understanding binding them to mutual support and a shared political agenda. In addition, the New Departure endorsed the Fenian movement and its armed strategies. Working together with Davitt (who was impressed by Parnell) he now took on the role of leader of the New Departure, holding platform meeting after platform meeting around the country. Throughout the autumn of 1879, he repeated the message to tenants, after the long depression had left them without income for rent:

Land League leader

Parnell was elected president of Davitt's newly foundedIrish National Land League

The Irish National Land League (Irish: ''Conradh na Talún'') was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which sought to help poor tenant farmers. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farmer ...

in Dublin on 21 October 1879, signing a militant Land League address campaigning for land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

. In so doing, he linked the mass movement to the parliamentary agitation, with profound consequences for both of them. Andrew Kettle

Andrew Joseph Kettle (1833–1916) was a leading Irish nationalist politician, progressive farmer, agrarian agitator and founding member of the Irish Land League, known as 'the right-hand man' of Charles Stewart Parnell. He was also a much admir ...

, his 'right-hand man', became honorary secretary.

In a bout of activity, he left for America in December 1879 with John Dillon

John Dillon (4 September 1851 – 4 August 1927) was an Irish politician from Dublin, who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for over 35 years and was the last leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. By political disposition Dillon was an a ...

to raise funds for famine relief and secure support for Home Rule. Timothy Healy followed to cope with the press and they collected £70,000 for distress in Ireland. During Parnell's highly successful tour, he had an audience with American President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

. On 2 February 1880, he addressed the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

on the state of Ireland and spoke in 62 cities in the United States and in Canada. He was so well received in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

that Healy dubbed him "the uncrowned king of Ireland". (The same term was applied 30 years earlier to Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

.) He strove to retain Fenian support but insisted when asked by a reporter that he personally could not join a secret society. Central to his whole approach to politics was ambiguity in that he allowed his hearers to remain uncertain. During his tour, he seemed to be saying that there were virtually no limits. To abolish landlordism

Concentration of land ownership refers to the ownership of land in a particular area by a small number of people or organizations. It is sometimes defined as additional concentration beyond that which produces optimally efficient land use.

Distri ...

, he asserted, would be to undermine English misgovernment, and he is alleged to have added:

His activities came to an abrupt end when the 1880 United Kingdom general election

The 1880 United Kingdom general election was a general election in the United Kingdom held from 31 March to 27 April 1880.

Its intense rhetoric was led by the Midlothian campaign of the Liberals, particularly the fierce oratory of Liberal leade ...

was announced for April and he returned to fight it. The Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

were defeated by the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

; William Gladstone was again Prime Minister. Sixty-three Home Rulers were elected, including twenty-seven Parnell supporters, Parnell being returned for three seats: Cork City

Cork ( , from , meaning 'marsh') is the second largest city in Ireland and third largest city by population on the island of Ireland. It is located in the south-west of Ireland, in the province of Munster. Following an extension to the city' ...

, Mayo Mayo often refers to:

* Mayonnaise, often shortened to "mayo"

* Mayo Clinic, a medical center in Rochester, Minnesota, United States

Mayo may also refer to:

Places

Antarctica

* Mayo Peak, Marie Byrd Land

Australia

* Division of Mayo, an Aust ...

and Meath. He chose to sit for the Cork seat. His triumph facilitated his nomination in May in place of Shaw as leader of a new Home Rule League Party, faced with a country on the brink of a land war.

Although the League discouraged violence, agrarian outrages grew from 863 incidents in 1879 to 2,590 in 1880 after evictions increased from 1,238 to 2,110 in the same period. Parnell saw the need to replace violent agitation with country-wide mass meetings and the application of Davitt's boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict som ...

, also as a means of achieving his objective of self-government. Gladstone was alarmed at the power of the Land League at the end of 1880. He attempted to defuse the land question with ''dual ownership'' in the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881

The Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881 (44 & 45 Vict. c. 49) was the second Irish land act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1881.

Background

The Liberal government of William Ewart Gladstone had previously passed the Landlord and Ten ...

, establishing a Land Commission

The Irish Land Commission was created by the British crown in 1843 to 'inquire into the occupation of the land in Ireland. The office of the commission was in Dublin Castle, and the records were, on its conclusion, deposited in the records tower t ...

that reduced rents and enabled some tenants to buy their farms. These halted arbitrary evictions, but not where rent was unpaid.

Historian R. F. Foster argues that in the countryside the Land League "reinforced the politicization of rural Catholic nationalist Ireland, partly by defining that identity against urbanization, landlordism, Englishness and—implicitly—Protestantism."

Kilmainham Treaty

Parnell's own newspaper, the ''United Ireland'', attacked the Land Act and he was arrested on 13 October 1881, together with his party lieutenants,William O'Brien

William O'Brien (2 October 1852 – 25 February 1928) was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of ...

, John Dillon, Michael Davitt and Willie Redmond

William Hoey Kearney Redmond (13 April 1861 – 7 June 1917) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP), was a lawyer and soldier Denman, Terence in: McGuire, James and Quinn, James (eds): ''Dictionary of Iris ...

, who had also conducted a bitter verbal offensive. They were imprisoned under a proclaimed Coercion Act

A Coercion Act was an Act of Parliament that gave a legal basis for increased state powers to suppress popular discontent and disorder. The label was applied, especially in Ireland, to acts passed from the 18th to the early 20th century by the Ir ...

in Kilmainham Gaol

Kilmainham Gaol ( ga, Príosún Chill Mhaighneann) is a former prison in Kilmainham, Dublin, Ireland. It is now a museum run by the Office of Public Works, an agency of the Government of Ireland. Many Irish revolutionaries, including the leade ...

for "sabotaging the Land Act", from where the ''No Rent Manifesto

The No Rent Manifesto was a document issued in Ireland on 18 October 1881, by imprisoned leaders of the Irish National Land League calling for a campaign of passive resistance by the entire population of small tenant farmers, by withholding rents ...

'', which Parnell and the others signed, was issued calling for a national tenant farmer rent strike

A rent strike is a method of protest commonly employed against large landlords. In a rent strike, a group of tenants come together and agree to refuse to pay their rent ''en masse'' until a specific list of demands is met by the landlord. This can ...

. The Land League was suppressed immediately.

Whilst in gaol, Parnell moved in April 1882 to make a deal with the government, negotiated through Captain

Whilst in gaol, Parnell moved in April 1882 to make a deal with the government, negotiated through Captain William O'Shea

Captain William Henry O'Shea (1840 – 22 April 1905) was an Irish soldier and Member of Parliament. He is best known for being the ex-husband of Katharine O'Shea, the long-time mistress of the Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell.

...

MP, that, provided the government settled the "rent arrears" question allowing 100,000 tenants to appeal for fair rent before the land courts, then withdrawing the manifesto and undertaking to move against agrarian crime, after he realised militancy would never win Home Rule. Parnell also promised to use his good offices to quell the violence and to

:co-operate cordially for the future with the Liberal Party in forwarding Liberal principles and measures of general reform.

His release on 2 May, following the so-called Kilmainham Treaty

The Kilmainham Treaty was an informal agreement reached in May 1882 between Liberal British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone and the Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell. Whilst in gaol, Parnell moved in April 1882 to make a ...

, marked a critical turning point in the development of Parnell's leadership when he returned to the parameters of parliamentary and constitutional politics, and resulted in the loss of support of Devoy's American-Irish. His political diplomacy preserved the national Home Rule movement after the Phoenix Park killings

The Phoenix Park Murders were the fatal stabbings of Lord Frederick Cavendish and Thomas Henry Burke in Phoenix Park, Dublin, Ireland, on 6 May 1882. Cavendish was the newly appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland and Burke was the Permanent ...

of the Chief Secretary Lord Frederick Cavendish

Lord Frederick Charles Cavendish (30 November 1836 – 6 May 1882) was an English Liberal politician and ''protégé'' of the Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone. Cavendish was appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland in May 1882 but was m ...

, and his Under-Secretary, T. H. Burke on 6 May. Parnell was shocked to the extent that he offered Gladstone to resign his seat as MP. The militant Invincibles responsible fled to the United States, which allowed him to break links with radical Land Leaguers. In the end, it resulted in a Parnell – Gladstone alliance working closely together. Davitt and other prominent members left the IRB, and many rank-and-file Fenians drifted into the Home Rule movement. For the next 20 years, the IRB ceased to be an important force in Irish politics, leaving Parnell and his party the leaders of the nationalist movement in Ireland.

Party restructured

Parnell now sought to use his experience and huge support to advance his pursuit of Home Rule and resurrected the suppressed Land League, on 17 October 1882, as the

Parnell now sought to use his experience and huge support to advance his pursuit of Home Rule and resurrected the suppressed Land League, on 17 October 1882, as the Irish National League

The Irish National League (INL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland. It was founded on 17 October 1882 by Charles Stewart Parnell as the successor to the Irish National Land League after this was suppressed. Whereas the Land League h ...

(INL). It combined moderate agrarianism, a Home Rule programme with electoral functions, was hierarchical and autocratic in structure with Parnell wielding immense authority and direct parliamentary control. Parliamentary constitutionalism was the future path. The informal alliance between the new, tightly disciplined INL and the Catholic Church was one of the main factors for the revitalisation of the national Home Rule cause after 1882. Parnell saw that the explicit endorsement of Catholicism was of vital importance to the success of this venture and worked in close co-operation with the Catholic hierarchy in consolidating its hold over the Irish electorate. The leaders of the Catholic Church largely recognised the Parnellite party as guardians of church interests, despite uneasiness with a powerful lay leadership. At the end of 1885, the highly centralised organisation had 1,200 branches spread around the country, though there were fewer in Ulster than in the other provinces. Parnell left the day-to-day running of the INL in the hands of his lieutenants Timothy Harrington

Timothy Charles Harrington (1851 – 12 March 1910), born in Castletownbere, Castletownbere, County Cork, was an Ireland, Irish journalist, barrister, Irish nationalism, nationalist politician and Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member o ...

as Secretary, William O'Brien

William O'Brien (2 October 1852 – 25 February 1928) was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of ...

, editor of its newspaper ''United Ireland'', and Tim Healy. Its continued agrarian agitation led to the passing of several Irish Land Acts

The Land Acts (officially Land Law (Ireland) Acts) were a series of measures to deal with the question of tenancy contracts and peasant proprietorship of land in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Five such acts were introduced by ...

that over three decades changed the face of Irish land ownership, replacing large Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

estates with tenant ownership.

Parnell next turned to the Home Rule League Party, of which he was to remain the re-elected leader for over a decade, spending most of his time at

Parnell next turned to the Home Rule League Party, of which he was to remain the re-elected leader for over a decade, spending most of his time at Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

, with Henry Campbell as his personal secretary. He fundamentally changed the party, replicated the INL structure within it and created a well-organised grass roots structure, introduced membership to replace "ad hoc" informal groupings in which MPs with little commitment to the party voted differently on issues, often against their own party. Or they simply did not attend the House of Commons at all (some citing expense, given that MPs were unpaid until 1911 and the journey to Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

both costly and arduous).

In 1882, he changed his party's name to the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish national ...

(IPP). A central aspect of Parnell's reforms was a new selection procedure to ensure the professional selection of party candidates committed to taking their seats. In 1884, he imposed a firm 'party pledge' which obliged party MPs to vote as a bloc in parliament on all occasions. The creation of a strict party whip

A whip is a tool or weapon designed to strike humans or other animals to exert control through pain compliance or fear of pain. They can also be used without inflicting pain, for audiovisual cues, such as in equestrianism. They are generally e ...

and formal party structure was unique in party politics at the time. The Irish Parliamentary Party is generally seen as the first modern British political party, its efficient structure and control contrasting with the loose rules and flexible informality found in the main British parties, which came to model themselves on the Parnellite model. The Representation of the People Act 1884

In the United Kingdom under the premiership of William Gladstone, the Representation of the People Act 1884 (48 & 49 Vict. c. 3, also known informally as the Third Reform Act) and the Redistribution Act of the following year were laws which ...

enlarged the franchise, and the IPP increased its number of MPs from 63 to 85 in the 1885 election.

The changes affected the nature of candidates chosen. Under Butt, the party's MPs were a mixture of Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

, landlord

A landlord is the owner of a house, apartment, condominium, land, or real estate which is rented or leased to an individual or business, who is called a tenant (also a ''lessee'' or ''renter''). When a juristic person is in this position, the ...

and others, Whig, Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

and Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

, often leading to disagreements in policy that meant that MPs split in votes. Under Parnell, the number of Protestant and landlord MPs dwindled, as did the number of Conservatives seeking election. The parliamentary party became much more Catholic and middle class, with a large number of journalists and lawyers elected and the disappearance of Protestant Ascendancy

The ''Protestant Ascendancy'', known simply as the ''Ascendancy'', was the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland between the 17th century and the early 20th century by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, and members of th ...

landowners and Conservatives from it.

Push for home rule

Parnell's party emerged swiftly as a tightly disciplined and, on the whole, energetic body of parliamentarians. By 1885, he was leading a party well-poised for the next general election, his statements on Home Rule designed to secure the widest possible support. Speaking inCork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

on 21 January 1885, he stated:

Both British parties toyed with various suggestions for greater self-government for Ireland. In March 1885, the British cabinet rejected the proposal of radical minister Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

of democratic county councils which in turn would elect a Central Board for Ireland. Gladstone on the other hand saying he was prepared to go 'rather further' than the idea of a Central Board. After the collapse of Gladstone's government in June 1885, Parnell urged the Irish voters in Britain to vote against the Liberal Party. The November general elections (delayed because boundaries were being redrawn and new registers prepared after the Third Reform Act) brought about a hung Parliament in which the Liberals with 335 seats won 86 more than the Conservatives, with a Parnellite bloc of 86 Irish Home Rule MPs holding the balance of power in the Commons. Parnell's task was now to win acceptance of the principle of a Dublin parliament.

Parnell at first supported a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

government – they were still the smaller party after the elections – but after renewed agrarian distress arose when agricultural prices fell and unrest developed during 1885, Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

's Conservative government announced coercion measures in January 1886. Parnell switched his support to the Liberals. The prospects shocked Unionists. The Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

, revived in the 1880s to oppose the Land League, now openly opposed Home Rule. On 20 January, the Irish Unionist Party

The Irish Unionist Alliance (IUA), also known as the Irish Unionist Party, Irish Unionists or simply the Unionists, was a unionist political party founded in Ireland in 1891 from a merger of the Irish Conservative Party and the Irish Loyal and P ...

was established in Dublin. By 28 January, Salisbury's government had resigned.

The Liberal Party regained power on 1 February, their leader Gladstone – influenced by the status of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

, which at the time was self-governing but under the Swedish Crown – moving towards Home Rule, which Gladstone's son Herbert revealed publicly under what became known as the "flying of the Hawarden Kite The Hawarden Kite was a famous British newspaper scoop of December 1885, that Liberal Party leader William Gladstone now supported home rule for Ireland. It was an instance of "kite-flying", made by Herbert Gladstone, son of the Leader of the Oppos ...

". The third Gladstone administration paved the way towards the generous response to Irish demands that the new Prime Minister had promised, but was unable to obtain the support of several key players in his own party. Lord Hartington

Spencer Compton Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, (23 July 183324 March 1908), styled Lord Cavendish of Keighley between 1834 and 1858 and Marquess of Hartington between 1858 and 1891, was a British statesman. He has the distinction of having ...

(who had been Liberal leader in the late 1870s and was still the most likely alternative leader) refused to serve at all, while Joseph Chamberlain briefly held office then resigned when he saw the terms of the proposed bill.

On 8 April 1886, Gladstone introduced the First Irish Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Bill 1886, commonly known as the First Home Rule Bill, was the first major attempt made by a British government to enact a law creating home rule for part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was int ...

, his object to establish an Irish legislature, although large imperial issues were to be reserved to the Westminster parliament. The Conservatives now emerged as enthusiastic unionists, Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill (13 February 1849 – 24 January 1895) was a British statesman. Churchill was a Tory radical and coined the term 'Tory democracy'. He inspired a generation of party managers, created the National Union of ...

declared, ''"The Orange card is the one to play"''. In the course of a long and fierce debate Gladstone made a remarkable Home Rule Speech, beseeching parliament to pass the bill. But the split between pro- and anti-home rulers within the Liberal Party caused the defeat of the bill on its second reading in June by 341 to 311 votes.

Parliament was dissolved and elections called, with Irish Home Rule the central issue. Gladstone hoped to repeat his triumph of 1868

Events

January–March

* January 2 – British Expedition to Abyssinia: Robert Napier leads an expedition to free captive British officials and missionaries.

* January 3 – The 15-year-old Mutsuhito, Emperor Meiji of Jap ...

, when he fought and won a general election to obtain a mandate for Irish Disestablishment

The Irish Church Act 1869 (32 & 33 Vict. c. 42) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which separated the Church of Ireland from the Church of England and disestablished the former, a body that commanded the adherence of a small min ...

(which had been a major cause of dispute between Conservatives and Liberals since the 1830s), but the result of the July 1886 general election was a Liberal defeat. The Conservatives and the Liberal Unionist Party

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

returned with a majority of 118 over the combined Gladstonian Liberals and Parnell's 85 Irish Party seats. Salisbury formed his second government – a minority Conservative government with Liberal Unionist support.

The Liberal split made the Unionists (the Liberal Unionists sat in coalition with the Conservatives after 1895 and would eventually merge with them) the dominant force in British politics until 1906

Events

January–February

* January 12 – Persian Constitutional Revolution: A nationalistic coalition of merchants, religious leaders and intellectuals in Persia forces the shah Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar to grant a constitution, ...

, with strong support in Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

, Liverpool, Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

and Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

(the fiefdom of its former mayor Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

who as recently as 1885

Events

January–March

* January 3– 4 – Sino-French War – Battle of Núi Bop: French troops under General Oscar de Négrier defeat a numerically superior Qing Chinese force, in northern Vietnam.

* January 4 – ...

had been a furious enemy of the Conservatives) and the House of Lords where many Whigs sat (a second Home Rule Bill would pass the Commons in 1893 only to be overwhelmingly defeated in the Lords).

Pigott forgeries

Parnell next became the centre of public attention when in March and April 1887 he found himself accused by the British newspaper ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' of supporting the brutal murders in May 1882 of the newly appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland

The Chief Secretary for Ireland was a key political office in the British administration in Ireland. Nominally subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant, and officially the "Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant", from the early 19th century un ...

, Lord Frederick Cavendish

Lord Frederick Charles Cavendish (30 November 1836 – 6 May 1882) was an English Liberal politician and ''protégé'' of the Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone. Cavendish was appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland in May 1882 but was m ...

, and the Permanent Under-Secretary, Thomas Henry Burke, in Dublin's Phoenix Park

The Phoenix Park ( ga, Páirc an Fhionnuisce) is a large urban park in Dublin, Ireland, lying west of the city centre, north of the River Liffey. Its perimeter wall encloses of recreational space. It includes large areas of grassland and tre ...

, and of the general involvement of his movement with crime (i.e., with illegal organisations such as the IRB). Letters were published which suggested Parnell was complicit in the murders. The most important one, dated 15 May 1882, ran as follows:

A Commission of Enquiry, which Parnell had requested, revealed in February 1889, after 128 sessions that the letters were a fabrication created by Richard Pigott

Richard Pigott (1835 – 1 March 1889) was an Irish journalist, best known for his forging of evidence that Charles Stewart Parnell of the Irish National Land League had been sympathetic to the perpetrators of the Phoenix Park Murders. Par ...

, a disreputable anti-Parnellite rogue journalist. Pigott broke down under cross-examination after the letter was shown to be a forgery by him with his characteristic spelling mistakes. He fled to Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

where he committed suicide. Parnell was vindicated, to the disappointment of the Tories and the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

.

The 35-volume commission report published in February 1890, did not clear Parnell's movement of criminal involvement. Parnell then took ''The Times'' to court and the newspaper paid him £5,000 () damages in an out-of-court settlement. When Parnell entered the House of Commons on 1 March 1890, after he was cleared, he received a hero's reception from his fellow MPs led by Gladstone. It had been a dangerous crisis in his career, yet Parnell had at all times remained calm, relaxed and unperturbed which greatly impressed his political friends. But while he was vindicated in triumph, links between the Home Rule movement and militancy had been established. This he could have survived politically were it not for the crisis to follow.

Pinnacle of power

During the period 1886–90, Parnell continued to pursue Home Rule, striving to reassure British voters that it would be no threat to them. In Ireland, unionist resistance (especially after the Irish Unionist Party was formed) became increasingly organised. Parnell pursued moderate and conciliatory tenant land purchase and still hoped to retain a sizeable landlord support for home rule. During the agrarian crisis, which intensified in 1886 and launched the

During the period 1886–90, Parnell continued to pursue Home Rule, striving to reassure British voters that it would be no threat to them. In Ireland, unionist resistance (especially after the Irish Unionist Party was formed) became increasingly organised. Parnell pursued moderate and conciliatory tenant land purchase and still hoped to retain a sizeable landlord support for home rule. During the agrarian crisis, which intensified in 1886 and launched the Plan of Campaign

The Plan of Campaign was a strategy, stratagem adopted in Ireland between 1886 and 1891, co-ordinated by Irish politicians for the benefit of tenant farmers, against mainly absentee landlord, absentee and rack-rent landlords. It was launched to c ...

organised by Parnell's lieutenants, he chose in the interest of Home Rule not to associate himself with it.

All that remained, it seemed, was to work out details of a new home rule bill with Gladstone. They held two meetings, one in March 1888 and a second more significant meeting at Gladstone's home in Hawarden

Hawarden (; cy, Penarlâg) is a village, community (Wales), community and Wards and electoral divisions of the United Kingdom, electoral ward in Flintshire, Wales. It is part of the Deeside conurbation on the Wales-England border and is home ...

on 18–19 December 1889. On each occasion, Parnell's demands were entirely within the accepted parameters of Liberal thinking, Gladstone noting that he was one of the best people he had known to deal with, a remarkable transition from an inmate at Kilmainham

Kilmainham (, meaning " St Maighneann's church") is a south inner suburb of Dublin, Ireland, south of the River Liffey and west of the city centre. It is in the city's Dublin 8 postal district. The area was once known as Kilmanum.

History

In th ...

to an intimate at Hawarden in just over seven years. This was the high point of Parnell's career. In the early part of 1890, he still hoped to advance the situation on the land question, with which a substantial section of his party was displeased.

Political downfall

Divorce crisis

Parnell's leadership was first put to the test in February 1886, when he forced the candidature of CaptainWilliam O'Shea

Captain William Henry O'Shea (1840 – 22 April 1905) was an Irish soldier and Member of Parliament. He is best known for being the ex-husband of Katharine O'Shea, the long-time mistress of the Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell.

...

, who had negotiated the Kilmainham Treaty, for a Galway by-election. Parnell rode roughshod over his lieutenants Healy, Dillon and O'Brien who were not in favour of O'Shea. Galway

Galway ( ; ga, Gaillimh, ) is a City status in Ireland, city in the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht, which is the county town of County Galway. It lies on the River Corrib between Lo ...

was the harbinger of the fatal crisis to come. O'Shea had separated from his wife Katharine O'Shea

Katharine Parnell (née Wood; 30 January 1846 – 5 February 1921), known before her second marriage as Katharine O'Shea, and usually called Katie O'Shea by friends and Kitty O'Shea by enemies, was an English woman of aristocratic background ...

, sometime around 1875, but would not divorce her as she was expecting a substantial inheritance. Mrs. O'Shea acted as liaison in 1885 with Gladstone during proposals for the First Home Rule Bill. Parnell later took up residence with her in Eltham

Eltham ( ) is a district of southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich. It is east-southeast of Charing Cross, and is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. The three wards of Elt ...

, Kent, in the summer of 1886, and was a known overnight visitor at the O'Shea house in Brockley

Brockley is a district and an wards of the United Kingdom, electoral ward of south London, England, in the London Borough of Lewisham south-east of Charing Cross.

History

The name Brockley is derived from "Broca's woodland clearing", a wood ...

, Kent. When Mrs O'Shea's aunt died in 1889, her money was left in trust.

On 24 December 1889, Captain O'Shea filed for divorce, citing Parnell as co-respondent, although the case did not come for trial until 15 November 1890. The two-day trial revealed that Parnell had been the long-term lover of Mrs. O'Shea and had fathered three of her children. Meanwhile, Parnell assured the Irish Party that there was no need to fear the verdict because he would be exonerated. During January 1890, resolutions of confidence in his leadership were passed throughout the country. Parnell did not contest the divorce action at a hearing on 15 November, to ensure that it would be granted and he could marry Mrs O'Shea, so Captain O'Shea's allegations went unchallenged. A divorce decree was granted on 17 November 1890, but Parnell's two surviving children were placed in O'Shea's custody.

News of the long-standing adultery created a huge public scandal. The Irish National League

The Irish National League (INL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland. It was founded on 17 October 1882 by Charles Stewart Parnell as the successor to the Irish National Land League after this was suppressed. Whereas the Land League h ...

passed a resolution to confirm his leadership. The Catholic Church hierarchy

The hierarchy of the Catholic Church consists of its bishops, priests, and deacons. In the ecclesiological sense of the term, "hierarchy" strictly means the "holy ordering" of the Church, the Body of Christ, so to respect the diversity of gif ...

in Ireland was shocked by Parnell's immorality and feared that he would wreck the cause of Home Rule. Besides the issue of tolerating immorality, the bishops sought to keep control of Irish Catholic politics, and they no longer trusted Parnell as an ally. The chief Catholic leader, Archbishop Walsh of Dublin, came under heavy pressure from politicians, his fellow bishops, and Cardinal Manning; Walsh finally declared against Parnell. says, "For the first time in Irish history, the two dominant forces of Nationalism and Catholicism came to a parting of the ways.

In England one strong base of Liberal Party support was Nonconformist

Nonconformity or nonconformism may refer to:

Culture and society

* Insubordination, the act of willfully disobeying an order of one's superior

*Dissent, a sentiment or philosophy of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or entity

** ...

Protestantism, such as the Methodists; the 'nonconformist conscience

The Nonconformist conscience was the moralistic influence of the Nonconformist churches in British politics in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Moral outlook

Historians group together certain historic Protestant groups in England as "Nonconfor ...

' rebelled against having an adulterer play a major role in the Liberal Party. Gladstone warned that if Parnell retained the leadership, it would mean the loss of the next election, the end of their alliance, and also of Home Rule. With Parnell obdurate, the alliance collapsed in bitterness.

Party divides

When the annual party leadership election was held on 25 November, Gladstone's threat was not conveyed to the members until after they had loyally re-elected their 'chief' in his office. Gladstone published his warning in a letter the next day; angry members demanded a new meeting, and this was called for 1 December. Parnell issued a manifesto on 29 November, saying a section of the party had lost its independence; he falsified Gladstone's terms for Home Rule and said they were inadequate. A total of 73 members were present for the fateful meeting in committee room 15 at Westminster. Leaders tried desperately to achieve a compromise in which Parnell would temporarily withdraw. Parnell refused. He vehemently insisted that the independence of the Irish party could not be compromised either by Gladstone or by the Catholic hierarchy. As chairman, he blocked any motion to remove him. On 6 December, after five days of vehement debate, a majority of 44 present led by Justin McCarthy walked out to found a new organisation, thus creating rival Parnellite and anti-Parnellite parties. The minority of 28 who remained true to their embattled 'Chief' continued in the Irish National League underJohn Redmond

John Edward Redmond (1 September 1856 – 6 March 1918) was an Irish nationalism, Irish nationalist politician, barrister, and Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. He was best known as lead ...

, but all of his former close associates, Michael Davitt, John Dillon, William O'Brien and Timothy Healy deserted him to join the anti-Parnellites. The vast majority of anti-Parnellites formed the Irish National Federation

The Irish National Federation (INF) was a nationalist political party in Ireland. It was founded in 1891 by former members of the Irish National League (INL), after a split in the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) on the leadership of Charles S ...

, later led by John Dillon and supported by the Catholic Church. The bitterness of the split tore Ireland apart and resonated well into the next century. Parnell soon died, and his faction dissipated. The majority faction henceforth played only a minor role in British or Irish politics until the next time the UK had a hung Parliament

A hung parliament is a term used in legislatures primarily under the Westminster system to describe a situation in which no single political party or pre-existing coalition (also known as an alliance or bloc) has an absolute majority of legisl ...

, in 1910

Events

January

* January 13 – The first public radio broadcast takes place; live performances of the operas '' Cavalleria rusticana'' and ''Pagliacci'' are sent out over the airwaves, from the Metropolitan Opera House in New York C ...

.

Undaunted defiance

Parnell fought back desperately, despite his failing health. On 10 December, he arrived in Dublin to a hero's welcome. He and his followers forcibly seized the offices of the party paper ''United Irishman''. A year before, his prestige had reached new heights, but the new crisis crippled this support, and most rural nationalists turned against him. In the December North Kilkenny by-election, he attractedFenian

The word ''Fenian'' () served as an umbrella term for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and their affiliate in the United States, the Fenian Brotherhood, secret political organisations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries dedicated ...

"hillside men" to his side. This ambiguity shocked former adherents, who clashed physically with his supporters; his candidate lost by almost two to one. Deposed as leader, he fought a long and fierce campaign for reinstatement. He conducted a political tour of Ireland to re-establish popular support. In a North Sligo by-election, the defeat of his candidate by 2,493 votes to 3,261 was less resounding.